“Morning, Sir. Did you sleep well?” It had been my custom to come straight to the point in addressing our foreign composer visitors, pretending to be cool and brisk. I know how busy they are and often, without exception I might say, lost in profound thought. This particular guest was, however, a rugged figure commanding unusually great deference with whom not even the ladies sitting behind him at concerts dared to argue (for his wig seemed to cover half the altar in Kuhmo Church). “Splendidly, thank you,” he replied, and I will concede that I did feel a modicum of pride that he was specifically speaking to me. “It’s an honour to play your music,” I further ventured to say, at which Herr Bach simply nodded with a gentle upward curve of his lips. That, at least, is how I wished to interpret it, but I’m sure the masters who had come to Kuhmo were pleased with what they heard.

The journey from the Church to the Salakamari is so short that it could almost be covered on all fours. I have to admit that things might sometimes have come to this, the Amati wines being unusually delectable, though treacherous at sunrise. Helping myself to a bowl of delicious borsch soup, I spotted our visitors over in a corner. Messrs Mahler, Strauss, Prokofiev and Shostakovich were sitting there savouring their soup, and the Russians appeared to have smothered theirs with sour Smetana’ cream. I may be wrong, but I seemed to sense a slight note of discord in the assembled company. I was just sprinkling my soup with salt (which was rare, as the kitchen fare was without exception magnificently seasoned), I heard Herr Prokofiev proclaiming in a loud voice about his work and its reception by the audience. “Il était le succès!” cried the cosmopolitan, while the silent Herr Shostakovich seated to his right gave the impression of having turned redder than the borsch in his bowl. Strauss and Mahler appeared to treat what they heard with German solemnity, though I also thought I detected a spark of friction between the two gentlemen. Strangely, the first signs of lightning!

I had heard a lot about Herr Beethoven, an unkempt character who, according to his older colleagues, was quite capable of losing his temper at rehearsals. “It says fortepiano, ach mein Gott!” he once thundered in the shadows of the Kuhmo Arts Centre, and I could feel the sweat break out around my fingers. I could see the unruly, bushy hair advancing on me like a giant across the platform and now, more than ever, I wished I could sink into the very depths of the septet we were practising. The unbroken silence was shattered like a drum skin as Herr Beethoven uttered in a voice a shade more lenient (I was in such a panic that I tried to see even a glimmer of light in the situation), “Fortepiano, no accent. If I want an accent, I’ll write an accent.” A life-long lesson: respect the composer’s wishes. You learn things in Kuhmo.

The sauna did not seem to appeal to all. I never had any problem sweating alongside my colleagues at the end of a hard day, though I must say there seemed to be more room on the benches for my butt some years ago (this is due to the life of an artist, so surely excusable!). Cooling off with a beer on the veranda after a sauna is nice, but this time I had something unusual to go with it: a Havana cigar! For as I gazed into the mirror-like surface of the lake beside the jetty, I was walking towards Herr Sibelius. There he stood, like a statue, and in the silence I could almost hear the whishing puffs of cigar smoke as they cut like a razor through the limpid air. As the sun sketched its rays on the clouds shimmering way across the lake he turned to me, raised his cut cigar, lit it and uttered words I will never forget: “Every note must live!” And that, if anything, is what happens here in Kuhmo. Tell me: could anything be more important? (Well maybe the construction of an extensive tram network in Kuhmo. The constant cycling for two weeks is, forgive the expression, a pain in the ass.)

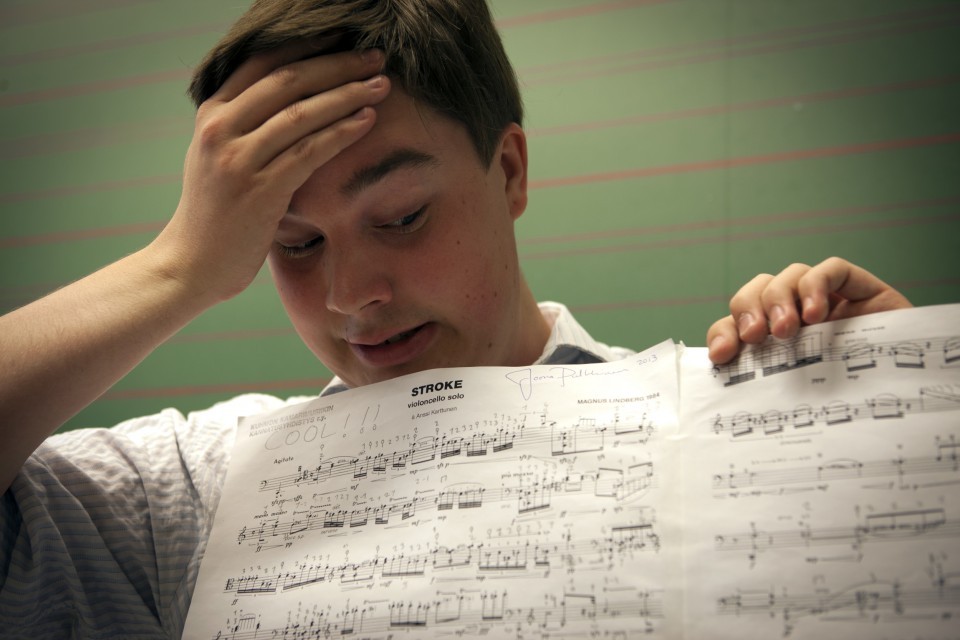

Joona Pulkkinen

2016